In an Ocean of Darkness

- Our Life Logs

- Mar 9, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Jun 24, 2020

| This is the 494th story of Our Life Logs |

Listen to the story on SoundCloud:

A bird loves to feel the wind in his wings and the clouds brushing his feathers as he flies. It is exhilarating. It is his life. But, when that bird’s wing breaks and he can never fly again, what defines his life vanishes before his eyes. Can such a broken spirit ever soar again? I found the answer to be “yes.” A “yes” in the most unbelievable way.

My life began in the Saudi Arabian city of Jeddah in 1962, a unique place nestled between the Red Sea and an expanse of desert. My hometown was a place where I spent a great deal of my childhood, but I also spent a few years in St. Louis, Missouri, as my father had to study abroad. Since those early years, it was my dream to leave the ground behind and work in an airplane. That dream surrounded me from all sides. My father was one of the first employees in Saudi Airlines. The house I grew up in was practically facing Jeddah’s old airport. Hearing the sounds of planes and seeing them flying high in the sky was as common to me as the constant flow of traffic to those growing up in big cities.

As I grew older, I saw my dream trickle into reality. In 1980, I found myself a crew member on Saudi Airlines. In my first four years working for Saudi Airlines, I was a flight attendant. Every day, I worked through a sea of people and faces, thousands of feet in the air.

Despite my childhood aspiration being fulfilled, things got even better a few years later when I became the first Saudi in-flight chef, or “Sky Chef” ― a job I had to fight to get. Saudis were not being hired at the time since we had no background in catering. However, motivated by the promise of frequent travel to New York City (one of my favorite cities in the world), I pushed until I was accepted in the training program. Soon, I found myself working as a Sky Chef for first class, where I exclusively went on flights going to and from New York.

During this time, my experience was enriched by the opportunities only that kind of job could offer. I was able to meet celebrities―actors, musicians, artists, and even an inventor of barbecue sauce, Ken Davis. And most amazingly, through a friend I met on a flight, I met my future wife from the state of Maine, US. We got married in 1986.

Flying to New York two times a month also allowed me to pursue my hobbies: mixing music, dancing, and photography. In fact, in some record stores, I was such a regular customer that the staff couldn’t believe I lived in Jeddah! My work in food preparation even became a new passion. I loved every moment cruising among the clouds and exploring New York on my downtime. Life was as beautiful as I had ever imagined.

After about three years as a Sky Chef, I noticed some issues in my vision, especially in the dark. After a visit to the eye doctor, I was diagnosed with shortsightedness, and something known as retinitis pigmentosa, or RP. Still, the condition was not such a big problem at the time. I was given a pair of glasses, and that was all. I could see, drive, and, most importantly, fly.

However, as my vision continued to worsen, I sensed my problem was not to stop there, and that realization tailed me like a storm cloud. I knew one day I would be grounded, never to work in the skies again. The only question was, “When?”

A few months later, my difficulties seeing in the dark developed into night blindness. It caused problems in my job with passengers and crew members alike, especially since the lights in the plane were dimmed, and we often flew at night. My doctor informed me that the RP was now affecting my retina more.

Four short years after the initial onset of the RP symptoms, I was grounded, just as I had feared. Despite the embarrassment and trials brought on by my deteriorating vision, the reality of being grounded was the most painful. The wonderful sensation of soaring in the sky, the dazzle of New York City, and the joy I got from my job of delivering the best first-class service to my passengers all disappeared in a moment. I was completely unprepared for this decision. I had no plan and no example to follow; after all, my situation was perhaps one of the first of its kind in the history of the airline.

Still, I stayed involved in food preparation, as Saudi Airlines gave me the position of a training instructor for in-flight chefs, a job I held for the next four years. During those four years, however, more darkness worked its way into my eyes, and more of the things I was working hard to hold onto slipped away. The steering wheel disappeared from under my fingers. Driving was gone. The pages of books could no longer be flipped through. Reading had vanished. The pen that was once gripped in my hand clattered soundlessly to the floor. Writing was taken away. The glasses I wore grew thicker and thicker until they were too uncomfortable to wear.

It was becoming hard to remain an instructor, not only from my fading vision but from the people I dealt with. To some, my condition was pitiful, while to others, it was even funny. I was a productive member of the training center, yet now I was becoming an inconvenience. My days were consumed by stress and, sometimes, anger, as my sight grew weaker.

To keep my job, I strove to prove myself as a model employee. One of the ways I did this was by helping develop “Meals for the Blind.” This was a service offered to visually-impaired passengers, which provided a menu and safety card in Braille, as well as special meals prepared so they could eat as independently as possible. Some foods, such as steak, were cut up before being served. I also developed a food service training program for the Saudi Navy, and trained 66 soldiers in two weeks’ time.

Despite all my efforts, the severity of my condition forced me into early medical retirement on October 15, 1992―which, coincidentally, was White Cane Safety Day.

Why does a bird have wings, a horse have legs, or a fish have fins? Because it is not only their dream to do what they do―fly, run, or swim―it is their life, their destiny, their purpose. If those appendages are removed, it is like taking away everything from them. That is how it felt when I was forced to leave my job. The dream which I had followed from childhood was gone. My passions, my hobbies, my life as I knew it, was swept away by an ocean of darkness.

Not only had I lost my eyesight and my job, but three days later, my first child, a son, was born with heart complications. The next few years was a blur of going back and forth between home and the hospital, worrying about his health. My sadness over losing my job was forgotten as I took on the new role of being a father and praying for him to survive. But once he was recovering, the scars from the shattered remains of my dream filled me with pain again. How would I help my new child? Could I pick up the pieces of my life, and find the wonder I once had?

The spark I was missing since my retirement found its way back in 1994 when I was on vacation in New York City. I visited a low-vision center, Lighthouse International, now known as Lighthouse Guild. There, I was given low vision care and, using special devices, I could read again for the first time in years. There, a new purpose, a new idea, was manifested: I wanted to do public service for those with visual impairments. Specifically, I wanted to do it in Saudi Arabia, since there was a lack of awareness, not to mention lack of resources.

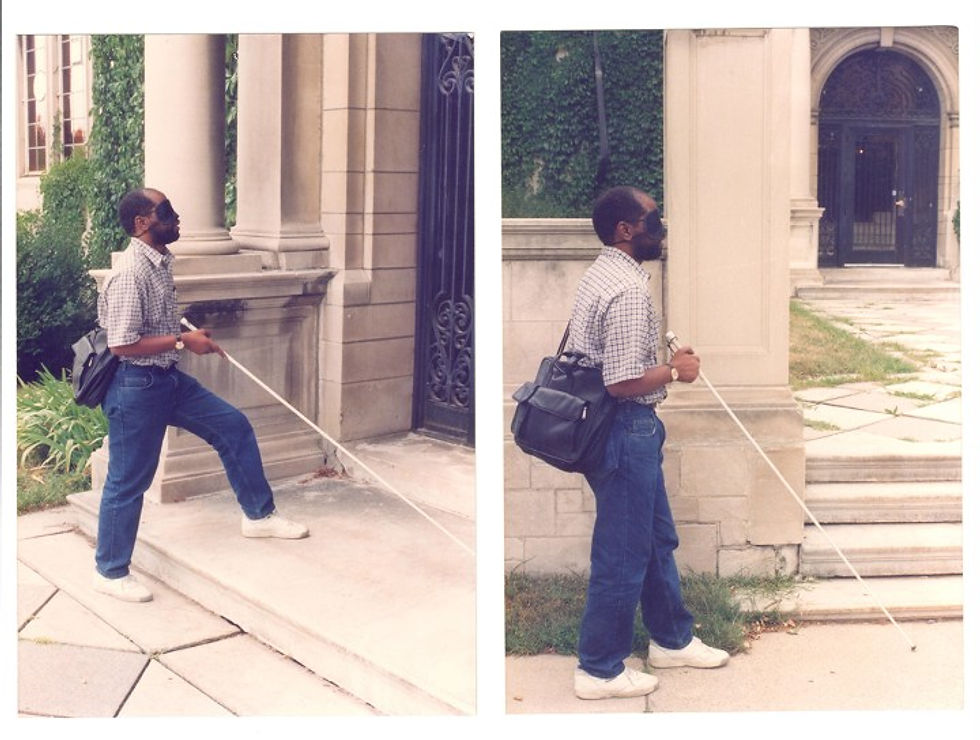

Finding that new life, that new light for my life, was what allowed me to turn in a new direction. But, how would I begin? That question nagged at me for two years, until a bolt of inspiration hit me. My wife learned about the National Federation for the Blind and their rehabilitation center in Minneapolis, BLIND Inc., which focused on total independence programs for the visually impaired. I enrolled in their program for one month; though I was recommended nine months, I couldn’t afford it. Still, those few weeks turned both my life and my thoughts around. I could live on my own in an apartment, go back and forth to the training center every day, and ride a bus independently.

Just that short time with BLIND Inc. gave me a wealth of information and skills which led me to a firm goal―beginning a vision rehabilitation center in Saudi Arabia. When I headed back home to Jeddah, I knew exactly what I wanted to do to help the visually-impaired community.

I began a campaign by utilizing the power of media. I had made a video about how I lived in Minneapolis and I took it to ART TV, the Arab Radio and Television Network. They incorporated my video into a documentary, My Journey Through the White Darkness, about my story of vision loss. In addition, I wrote a proposal to open a center to help rehabilitate and teach people of all ages with low vision life skills. Both the film and the proposal were met with incredible support. With the invaluable help of multiple sponsors―namely, Lighthouse Guild, Prince Talal Bin Abdul Aziz, the presidents of the Islamic Development Bank and the Maghrabi Hospital―I was able to push this idea into reality. Low vision programs were launched first, and the center, the Ebsar Foundation, was officially founded in 2003.

I found myself back to work at the center I helped build. In my job, I was not “on the field”, but rather, I held a desk job, something I wasn’t used to. Still, it gave me a chance to reflect. In the midst of my retrospection, I was struck with another idea. Using my closed-circuit television, which helped me in reading and writing, I penned a book about my experience, Harvest of the Darkness―the first of several books.

My team and I tirelessly continued to improve Ebsar’s services. It now not only rehabilitates those with low vision, but it also trains professionals to run the programs and the clinic. In 2016, we launched an early detection campaign for childhood eye diseases, using a program called Eye Spy, a software program which lets children play a game on a regular laptop.

Through my awareness campaigns and writing, I hope to help people with visual impairments throughout their journeys, from the rocky beginning to the hopeful middle. Those whose vision fades need—more than anything—a soft hand and a guiding light, especially in the beginning. They need to know what I now know―they are not a bird robbed of its wings, even though it feels as if the sky is torn away. Their dreams are not sand that a shadowy wind scattered away. This block in their path does not toss them to the ground to stay. Instead, they are as strong as before, and perhaps stronger, especially with a white cane in hand.

This is the story of Mohammed Towfik Bellow

Mr. Towfik was born in 1962 with a head full of dreams, dreams that literally reached the sky. In 1980, he found himself working as a flight attendant for Saudi Airlines, and later, the first Saudi Sky Chef. However, a few years later, he was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa…and his dreams faded into darkness. After getting forced into medical retirement, Mr. Towfik had no idea what to do. After a visit to two US-based low vision centers, he proposed and successfully founded the Ebsar Foundation for rehabilitation and low-vision services. In 2015, he resigned from Ebsar to pursue his writing and be an independent consultant. Since then, he has penned five books and hopes to publish two more in 2020. He also is a weekly column writer and discusses a variety of topics. Recently, Mr. Towfik has received the United African and Arabs Achievement Award for 2019 in Cairo, Egypt. This award was in recognition for his contributions in Arab literature and journalism as well as his work in vision rehabilitation. He strives to inspire people to have hope and faith, no matter what they face.

This story first touched our hearts on February 18, 2020.

| Writer: Safiyya Bintali | Editor: MJ |

Comments